TV Venkateswaran

With the rise of the knowledge economy and the need for a learning society, highly qualified human capital is essential, necessitating the advancement of higher education, science, and technology. As pointed out in the NITI Aayog’s India Innovation Index-2021 report, numerous studies have shown a positive association between per capita R&D expenditure and per capita GDP, with nations with high per capita R&D expenditure also having higher per capita GDP. Kaur and Singh (2016) examined 23 emerging economies (including India) from 1991 to 2010, finding that even a 1% increase in R&D expenditure results in 0.30% economic growth. Evenson and Singh (1997) found that a country’s R&D expenditure positively influences its output after reviewing data for 11 Asian countries from 1970 to 1993.

The founding leaders of newly independent India saw the importance of science and technology in addressing their challenges, which included public health, poverty, unemployment, and underdevelopment. The Scientific Policy Resolution of 1958 stated that “the dominating feature of the contemporary world is the intense cultivation of science on a large scale, and its application to meet a country’s requirements”. It argued that “it is only through the scientific approach and method and the use of scientific knowledge that reasonable material and cultural amenities and services can be provided for every member.”

The edifice of the Indian scientific ecosystem was created modestly, brick by brick. The policy’s implementation was marked by the establishment of key organisations such as the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), laying the foundation for research and development in various sectors, with a focus on building scientific infrastructure and human resources.

If we look at our achievements, such as being the preferred destination for ‘health tourism’ or the high number of H-1B visas issued to Indian nationals, we can see the potential for further growth. The seeds we have planted are bearing fruit now, and there is still more to be harvested.

The old public health concerns, poverty, unemployment, and underdevelopment have been augmented by emerging ones, such as global warming, the energy crisis, and environmental degradation. We must become ‘friends with science’ now more than ever.

However, recent trends are worrying and raise the question of whether the fruit-bearing plants will continue to be nurtured and cared for and whether the grove will be sown with fresh seeds to meet future demands. This is the key question facing us.

Where are we?

If we go by the policy pronouncements, nothing is lacking. The Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy of 2013 said that it has long been a national aim to boost gross expenditure on research and development (GERD) to 2% of GDP, as well as to “increase the number of R&D personnel by 66% in the next five years.” The most recent draft of the Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy 2020 proposes “to double the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) researchers, gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD), and private sector contribution to the GERD every five years.” If this was true, the future is bright. We would be not only sustaining our old gains but also breaking new ground. There would have been adequate human and financial resources for science, technology and innovation. Nevertheless, sadly, there is a significant gap between policy and practice.

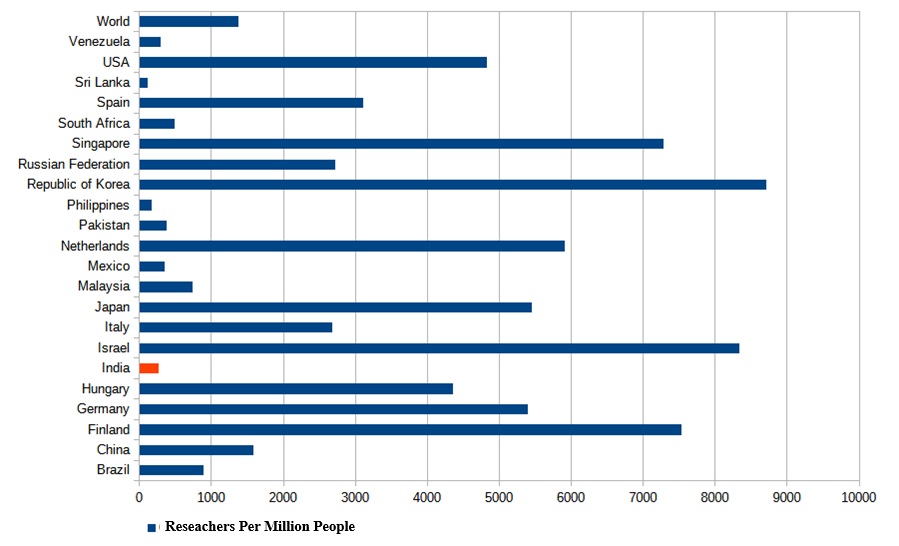

Human resources are critical for science and innovation. Unfortunately, India has far fewer researchers per million inhabitants, at 262, than many other countries. It is superfluous to argue that without an appropriate number of researchers, India’s goal to catch up with the industrialised world and become an economic superpower will be a pipe dream. We will not even be able to provide basic necessities to all our fellow citizens. Figure 1 depicts India’s “researchers per million” compared to other selected countries. Forget China and the other BRICS+ nations; it is a pity that we not only fall significantly below the global average but also lag behind our closest neighbour. The numbers are not growing fast enough; they are lingering, causing despondency.

Trends in higher education

The key to boosting the number of researchers in our country lies in the active participation of our youth in higher education and research. Each individual’s contribution is crucial, and by expanding higher education and attracting students from all backgrounds, we can build a stronger, more inclusive research community. Without increased funding for higher education and science, providing adequate instruction and job facilities will be difficult.

What are the recent trends in higher education and funding for research and innovation? PRS Legislative Research is an Indian non-profit organisation founded as an independent research institute to enhance the Indian legislative process. They have frequently analysed budgets and provided insightful analysis. They prepared two reports: “Demand for Grants 2024-25 Analysis: Science and Technology” and “Demand for Grants 2025-26 Analysis: Education.” This short note is essentially a review of these two reports.

NEP (2020) ambitiously aims to increase the gross enrolment ratio (GER) in higher education to 50% by 2035. The gross enrolment ratio (GER) in higher education is the percentage of students enrolled relative to the total population aged 18 to 23. This is a measure of youth participation in education. Indeed, expanding higher education is critical to producing a competent, skilled workforce. One would anticipate that some of these youngsters would be drawn to research, strengthening the scientific and innovation workforce. However, the outlook for higher education in the country is dark and grey. Some states, like Tamil Nadu (47%) and Kerala (41%), are on track to meet this aim. Nonetheless, the GERs of states such as Bihar (17%), Jharkhand (19%), and Uttar Pradesh (24%) lag behind, raising the question of whether they would be able to sprint to fulfil the NEP objective. Given the reality, the target of 50% GER by 2035 looks like a faraway dream.

If wishes were horses, we could ride our way to educating our country’s youngsters with wannabe, grandiose educational policy pledges. However, significant public expenditure is required to draw more young people to higher education. Unfortunately, governmental investment in the sector of higher education does not meet our aspirations.

With governmental funding in higher education declining, aspiring students are forced to attend more expensive private institutions. But this is not an option for everyone.

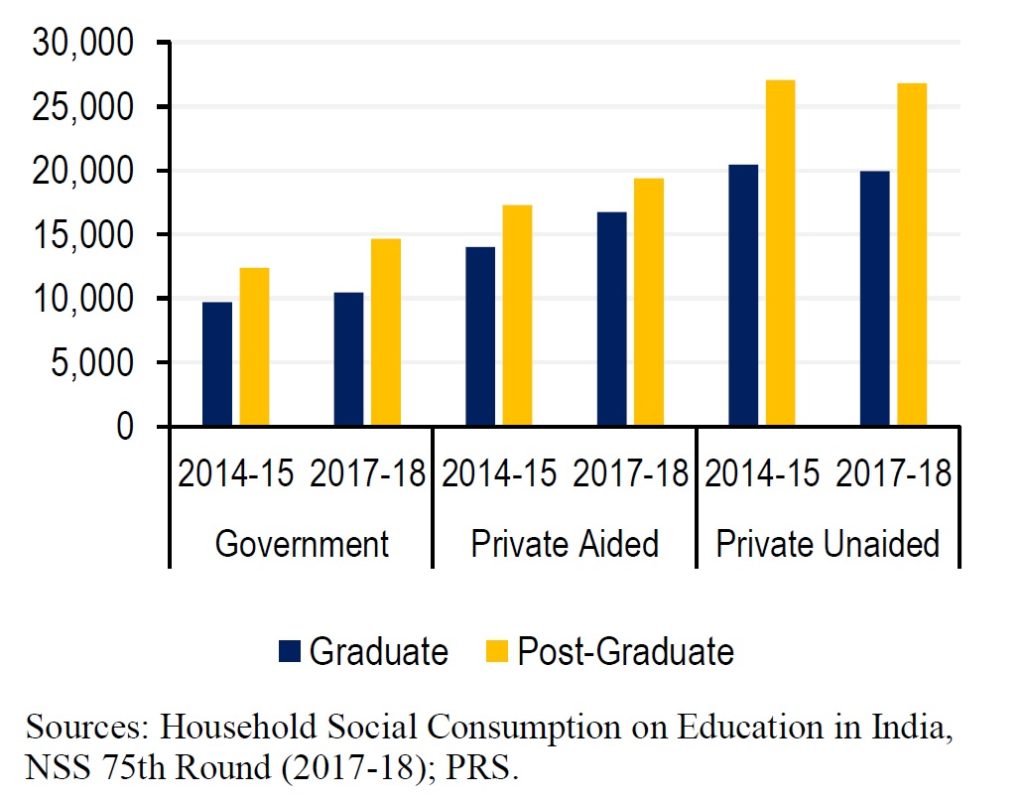

In 2021-22, 78% of all colleges are privately owned, with 66% of college enrolment in privately run institutions. According to the NSS (2017-18), the cost of studying at a private, unaided higher educational institution (HEI) was about twice that of a government university (see Figure 2). A detailed report of the NSS 2002 survey is yet to be released. Nonetheless, after examining the trends, a recent paper by Motkuri, V. and E. Revathi (2020) states that the growth in public expenditure on education was higher than that of private during the first four decades, from the 1950s through the 1980s, but thereafter, from 1990s through the present decade, it is the reverse. The ratio of public to private expenditure in education has increased from 0.7 in 1951-52 to whooping 1.6 in 2019-20. Such a trend reflects the increasing privatisation of education in India and has far-reaching policy implications.

Given that the poorest members of society have yet to enter higher education, expensive private institutions will discourage youth from economically and socially disadvantaged backgrounds from enrolling in Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs). As a result, the GER will not grow.

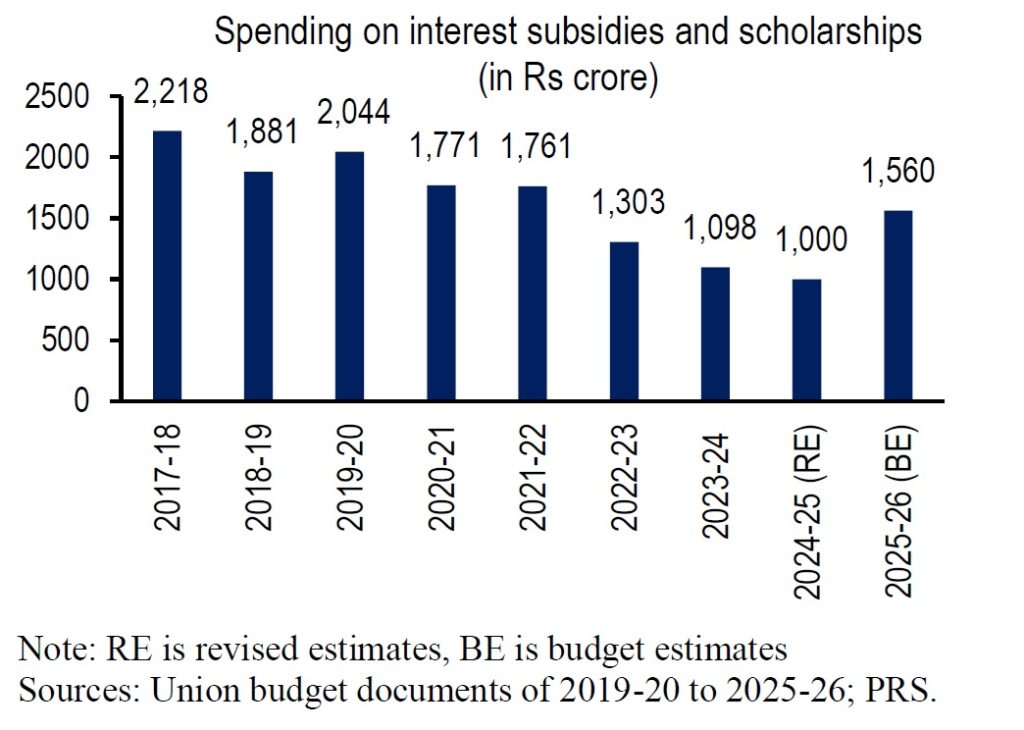

To add insult to injury, the PRS study reveals that the Union Government’s investment in scholarships and interest subsidies is dropping, imperilling the participation among females and socially and economically disadvantaged groups, making the ideal of 50% GER even more distant (see Figure 3).

The government covers nearly 34% of the cost of education in private HEIs in OECD countries through scholarships and loans. Even in the United States, where universities are administered mainly by private interest, endowments bear 33% of the expense. With shrinking scholarships and rising higher education costs, achieving 50% GER is becoming an increasingly distant goal.

Unfilled teaching positions

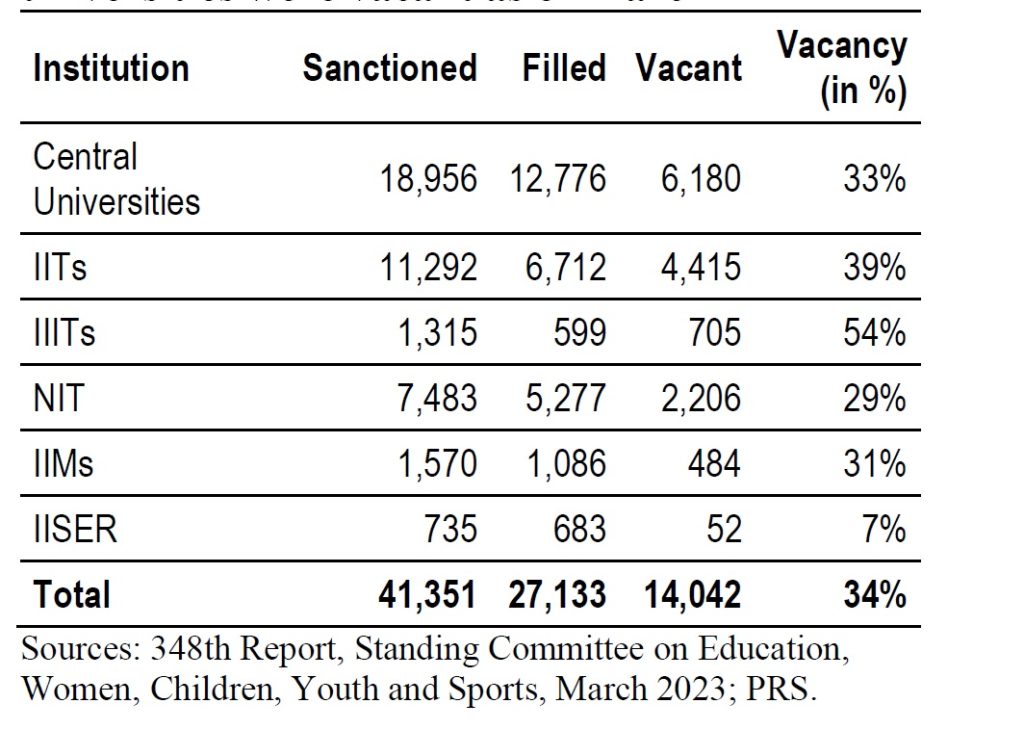

Academic positions in educational institutions help to increase the pool of researchers, improve training, and give jobs, consequently creating a promising employment ecosystem to attract talented young people to science and innovation. As of March 2023, more than one-third of positions at centrally funded institutions were vacant, resulting in a negative environment (see Figure 4). According to reports, the empty posts are still unfilled due to a lack of funding. However, we can observe that the money allocated for higher education is not adequately used. For example, the revised projections for 2024-25 of Rs 46,482 crore are lower than the budget estimate of Rs 47,620 crore for higher education. In 2024-25, more than 1200 crore will be spent, less than the planned amount. This money may have boosted teacher appointments at higher education institutions.

Dwindling investment in science

In the scientific and technology area, public announcements and remarks are pleasant. According to media sources, the union budget for 2025-26 includes a significant investment in research and innovation. The Hindu newspaper stated, “Union Budget 2025: Science Ministry gets a hefty hike powered by corpus to finance private R&D” and continued: “Budget allocation of 20,000 is almost triple the usual amount; will be used to fund the private sector and startups in sunrise sectors, says DST Secy; currently, less than 1% of GDP spent on R&D due to low private participation”. Indeed, the main four scientific and technology ministry/departments’ budget projections for 2025-26 (DST -28508.90, DBT 3446.64, DSIR/CSIR 6657.78, and MOES 3649.81) are much higher than the previous year.

However, the devil is in the details. Budget forecasts have recently lost their sanctity; they are now viewed mostly as a wish list with pomp. The reality lies in the specifics, or what is known as ‘actuals’; that is, the amount ‘actually’ issued and spent on the budget item. First, the budget forecasts are ‘ revised’ based on ‘actual’ cost spent in mid-course, around November. The ‘actuals’ represent the actual spending released. As a result, actuals are often lower than revised projections, which are significantly lower than budget estimates.

Let us look at the track record for 2024-25 in Table 1. The actuals for 2024-25 have yet to be determined. We just have the budget estimate and a revised estimate.

Table 1: The 2024 budget of the Science and Technology Ministry at a glance

| Organisation | Budget Estimate ( in crores) | Revised Estimate ( in crores) | Difference in percentage |

| DST | 8029.01 | 5661.45 | 70.51 |

| DBT | 2275.00 | 2460.13 | 108.14 |

| DSIR/CSIR | 6323.41 | 6350.54 | 100.43 |

| MOES | 3064.80 | 3632.78 | 118.53 |

The rise in MOES RE is attributed to increased capital outlay, whereas the variances in DST, DBT, and DSIR RE are related to revenue. Now, let us delve further. DST is one of the primary financing agencies for science and technology initiatives. The money was initially allocated through SERB and later NRF. The TDB is also an important agency that grants research funding.

Table 2: The 2024 budget of key funding agencies of DST at a glance

| Budget Estimate ( in crores) | Revised Estimate ( in crores) | Difference in percentage | |

| SERB | 803 | 766 | 95.39 |

| TDB | 100 | 6 | 6 |

| NRF | 2000 | 200 | 10 |

Interestingly, the budget estimates for SERB for 2025-26 are only 693.25, TDB 7, and NRF 2000.

The stark contrast between what is announced in the budget and what is actually released for spending is clear. Table 3 shows the budget estimate and actual expenditures. Real spending has significantly declined recently, resulting in a severe drop in research support.

Table 3: Budget estimate and the actual investment of DST

| Budget Estimates | Revised Estimates | Actual | Percentage of actuals over budget estimates | |

| 2019-20 | 5600 | 5501 | 5453 | 97.38 |

| 2020-21 | 6313 | 5012 | 4913 | 77.82 |

| 2021-22 | 6071 | 5244 | 5146 | 84.76 |

| 2022-23 | 6002 | 4907 | 4436 | 73.90 |

| 2023-24 | 7932 | 4892 | 61.67* |

* based on RE

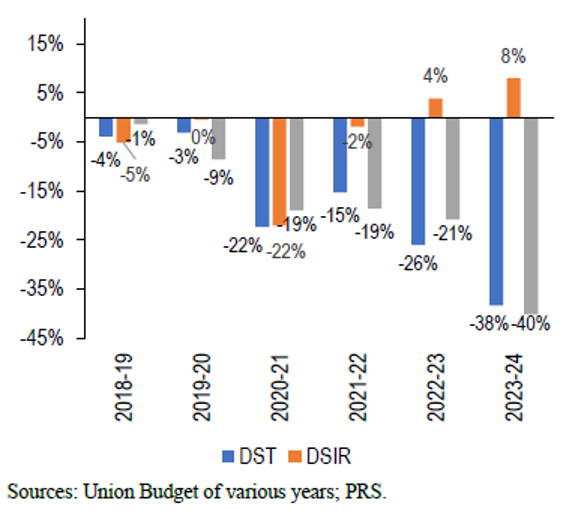

This has been the pattern over the previous few years, as seen in Figure 5. What was once a 3 to 5% disparity has slowly expanded, and by 2023-24, it was a whopping 38-40%! Despite apparent budget increases, the research community’s fear that financing has become increasingly limited in recent years appears correct.

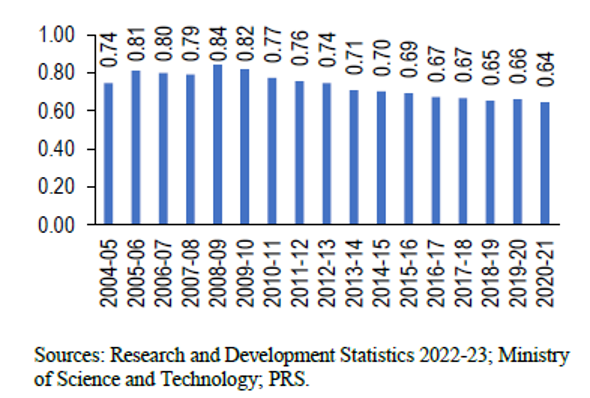

However, these four core institutions are not the only agencies that support research. Business enterprises, higher education institutions, governments, and private non-profit groups all fund research, often in tiny ways. Investment in science and technology research, including all entities’ expenditures, is quantified in terms of gross research and development expenditure (GERD). Since 2009-10, the GERD as a proportion of GDP has been steadily declining (see Figure 6).

Glory and Gore

India’s spectacular successes in the space sector, such as landing on the Moon and developing cryogenic engines, are supplemented by considerable effort in other fields of science, technology, and innovation that are mostly unnoticed by the public. However, these are equally important to our economy’s growth and our citizens’ well-being. These are just the rewards of previous generations’ efforts. Failure to supply consistent nutrition will cause withering and stunted development.

Unfortunately, few new institutions have been founded in the recent two decades, except for name changes or ‘mergers’. Most legacy institutions were formed at least two to three decades ago. Unfortunately, when demand exceeds supply, many institutions and research units close. Of course, one must update and reposition in response to changes in technology and emphasis, but if closures are not accompanied by adequate new seeding, the research ecosystem will inevitably decline. All central funding is proposed to be routed through ANRF. Such centralisation will seriously hamper the timely evaluation and dispersal of funds. Also, the line departments will be hampered in seeking research in areas of their immediate interest.

In key technological areas, we seem to be happy with imports and reliance on others, compromising self-reliance, admanirbar, make-in-India, and security. Take the case of 6G; we are rushing head-on for its implementation without any basic R&D in relevant areas. The same is the case for AI. The allocation of Rs 2,000 crore for the IndiaAI Mission for 2025-26, which is nearly a fifth of the scheme’s total outlay of Rs 10,370 crore, is made in this budget. The outlay itself is suboptimal; billions are required to develop LLMs. If we do not gear up and mobilise the resources, we will miss this bus, too.

Science and technology are swiftly evolving, and as the Red Queen once said, one must run faster to merely stay in the same location. The patterns observed over the last two decades are not promising or inspiring. Will this budget alter the path of higher education, science, technology, and innovation? We have no option but to keep hoping.

References

- Evenson, R. E., & Singh, L., (1997). Economic Growth, International Technological Spillovers and Public Policy: Theory and Empirical Evidence from Asia. Centre Discussion Paper, No. 777, Yale University, Economic Growth Centre, New Haven, CT.

- India Innovation Index 2021, Niti Ayog (Source Link)

- Kaur, M. & Singh, L. (2016). R&D Expenditure and Economic Growth: An Empirical Analysis. International Journal of Technology Management & Sustainable Development, 15(3), 195-213

- Motkuri, V. and E. Revathi (18 September 2020). Private and Public Expenditure on Education in India: Trend over last Seven Decades, CESS-RSEPPG Research Brief #2, Research Cell on Education (RSEPPG), Centre for Economic and Social Studies, Hyderabad

- PRSIndia Demand for Grants 2024-25 Analysis: Science and Technology (Source Link)

- PRSIndia Demand for Grants 2025-26 Analysis: Education (Source Link)

- S&T Indicators Tables Research and Development Statistics 2022-23, Department of Science and Technology (Source Link)

Dr. T. V. Venkateswaran is a science writer, science communication trainer, and visiting professor at IISER Mohali.

Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of Confluence, its editorial board or the Academy.