The COVID-19 pandemic has been harsh on everyone, albeit to different levels: professionals and their marketplaces, our education systems, our daily wage workers, and especially on marginalized communities. While hoping for science to come up with a solution, many have professed that it will change the way we live, creating a new normal. Huge number of deaths even in developed economies has bared how disproportionately we are divided into the haves and have-nots; be it economic stability, racial/status divide or the ability to personalize healthy living and immunity. But there is that unanimous question: “Why is the solution taking so long?”. Never before have scientists worked so collaboratively across borders, that helped bare the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2). Even though time is of essence, it is because of the rigorous scientific method of clinical trials we use today, that there are no shortcuts. Albeit this fact, I will further argue, that there is an unseen underbelly to this question, and that answer is neither forgiving nor straightforward.

The core question I propose to discuss is “What makes the science and the scientist themselves vulnerable, en route to such discoveries in COVID times”? Everyone would agree that better funding and planning for infrastructure, along with an influx of fresh ideas, would help buffer us in times of need. Yet, the ground realities about the relationship between policy makers and stakeholders seems further than resolved. Even after seven decades of independence, why so? A large part of this discussion will focus on the qualitative learnings from history and reflect on how we can apply those in post-COVID times.

Part 1 – Science as the strategy: where we are today

Early beginnings to the industrial revolution

Food, clothing, and shelter form the bedrock of any civil society. Any surplus thereof, created ‘wealth’, which allowed societies to devote time towards developing creativity in science and the liberal arts. When channelized by great vision and leadership, these add back to the economies, developing them further. Throughout millennia, nations and political movements have evolved to understand and control this ebb and flow. Early colonial rulers recognized this ‘wealth’ and encouraged fundamental science and exploration. This helped discovery of the new world and kick started the two industrial revolutions in the west. “Black gold” and the steam-engine enabled robust transport mechanisms to draw raw material through world-wide slavery. Breaking free of imperialism and riding the wave of free market economy, the U.S.A. emerged as a beacon of democracy and capitalism. The quintessential “American dream” became a reality for many. While newly independent Asian and African nations struggled for daily bread, they also invested in education as the eventual solution. However, a lack of infrastructure to execute new scientific ideas and a promise of a better life abroad, drove many of these newly educated to the west, depleting intellectual property (IP) from the very nations that educated them. As a result, nearly 40% of US Nobel laureates (Sciences) in the last 20 years have been immigrants. Having recognized this early on, the post-colonial west welcomed immigrants and invested a significant part (2.5-3 %) of their growing GDP into science, further fueling the cycle.

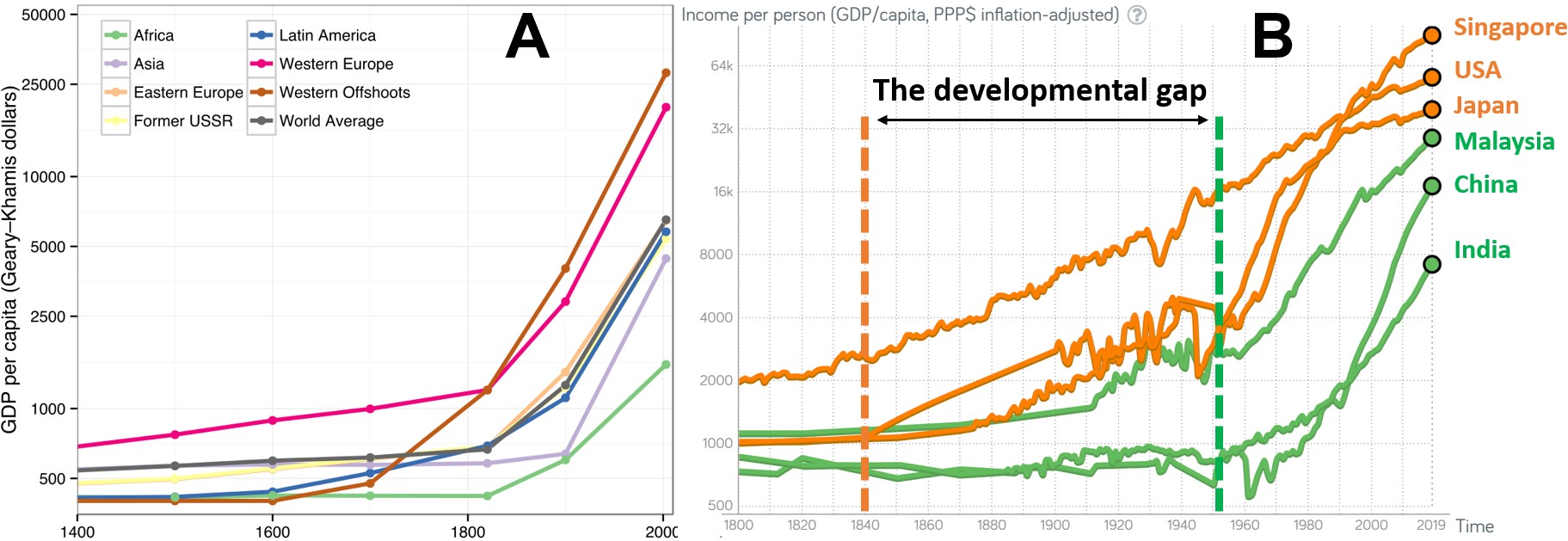

Democracy wasn’t problem free either. Even though ‘free market competition’ should in-principle correct itself, the realities of monopolization and government lobbying by the behemoths, seemed to offer a “perceived” version of democratic choice. New innovations which break these cycles of monopoly are becoming increasingly infrequent, especially with the liberalization of corporate mergers and take-overs. The epic tales of Tesla versus Edison ring similes; history seemingly replete with examples even more relevant today. Income-inequality seems to be at historic highs in this “free world”. It is no surprise therefore that some believe in a socialist solution, that enshrines more regulation and re-distribution of resources, since those at a better vantage point never seem to recognize their pre-existing privilege (the rich get richer). Nothing brings fore this argument better, than the climate crisis we face today. Two centuries of energy-hungry progress benefitted the developed nations; a cost that they now want everyone to incur by regulating responsibly, going forward. Having benefited from a much smaller piece of the fossil-fuel pie, mid-income countries like India particularly feel disadvantaged. In the last 30 years of globalization, when the country seems to have finally gotten a foothold, the ‘privileged’ (class?) don’t seem to recognize the spoils they stand on, and give us our due. Have we missed the development bus? Is it too late?

Figure 1: Graphical representation of GDP growth: (A) across world economies from 1400 – 2019 (source: Wikicommons), (B) selected comparison of three large (orange) and medium (green) sized economies from 1800-2019 (source: GAPminder). Note: Since the Y-axis in both graphs is logarithmic, the differences are much larger than they appear to the eye.

Science in modern India

Unsurprisingly, from Charaka to Bhaskaracharya, scientific contributions in ancient India came from the ‘educated’ cream of the Varna system. Mathematical treatises developed largely for religious purposes found applications in trade and agriculture; rather than to objectively derive fundamental laws of the universe. Cycling education among the elite top of the caste pyramid, limited the diversity of ideas, evident today as voids in the historical continuity of scientific thought. Three millennia later, having lost its material riches to centuries of invaders and 200+ years of colonial rule, post-independent India had a huge poverty problem at hand. Socialistic policies tried to ensure that school education be practically open to all. Some elites did benefit by seeking institutes of higher learning abroad. Albeit its socialist grain, in order to produce high quality science, earlier governments stressed the need to focus its limited resources into a handful of research institutions. These however stayed functionally disconnected from the broad university base, that housed the doyens of classroom teaching, what I would qualify as bookish or even rote. This served to rapidly ‘educate’ and create the much-needed manpower. As a philosopher once said, “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn”. This separation of the practice of science from the larger ambit of education not only created a populace largely lacking the expertise to innovate, but also dwarfed their ability to query with an open mind, limiting our understanding of the scientific method. Further fueled by our cultural context where hierarchy is revered and textbooks become dogmatic truth, a youngster who questions senior authority is looked down upon as being disrespectful, or even deviant. Breaking free off these shackles of centuries of conditioning (a slew of reasons, impossible to cover in this discussion) is not easy. With limited access to higher learning, we never really generated the critical numbers of scientists that a developed nation could achieve. Having been deprived off new role models to look up to, such societies began to look inward, taking respite in their glorious past. With limited resources and little to celebrate, nationalistic fervor clung to historical reverence and empirical method of the ancients. It seems, the time is ripe, to recall one of the eleven constitutional duties enshrined for every citizen of India – to maintain scientific temper. How long can we remain victims to cycles of privilege? India opened-up to a global free-market economy, slowly losing its socialist grip – Could we recreate the American dream at home?

The free market and science funding:

Science can be broadly classified into one that is fundamental in nature and largely curiosity driven (blue sky research), while the other is utilitarian, where the taxpayer gets tangible benefits in return. The connection is often not apparent to policy makers: By asking Fundamental or sometimes even uncomfortable questions, basic scientists discover new principles, which are then used in innovative ways by applied scientists to design novel technologies that help drive capitalist markets. Many such technologies in turn, enable basic researchers with new tools, making discovery and innovation interdependent; the two crutches of scientific progress. The problem is that the applications are often different or too far-reaching than the basic research it originally stemmed from. Did Newton think “….just maybe, if I know why this apple fell from the tree, I will figure out how to colonize Mars!!!”? …in all humility, I would say, probably not! It is this incongruent connection, that makes fundamental research ever more vulnerable to getting hacked off-the-list by free-market funding, typically driven by capitalistic demand. Public funding is therefore critical to create this balance. It is this seemingly undemocratic treatment of science funding by a democratically elected government that defines their vision and the future trajectory of their people. Keeping these aspects and limited resources in mind, one can now introspect; how did independent India’s gamble pay off?

Socialist policies in education and development from the 1960’s to mid-80’s laid the foundation for a ready manpower towards IT and globalization policies. As a result, in the next four decades, India’s per-capita GDP steadily went up. As the pie grew, net science funding did increase, but the percent contribution of the pie did not change. Not only did it fluctuate around a meagre 0.7% for 70 years, of late it has been at a low of ~0.6%; about 4-5 times lower than China or US and almost eight times lesser than South Korea (which handled COVID-19 quite effectively). As demands for higher learning in India keep increasing, will the concomitant decrease of adequate funding per researcher reinstate brain-drain? The Indian problem is further exacerbated with abysmally poor investments from the private sector. Compared to every government dollar that is matched by $6.3 invested by the US and $4.9 by the Chinese market enterprises, private investments in Indian science appear puny ($0.66). In hindsight one can either blame the lack of policy/tax-incentives for the private sector or an even deeper anathema of bookish education, that probably left Indian capitalists clueless of how basic research fuels economies. Scientists stayed in their academic cocoons, failing to cross over and communicate the scientific method to the masses. In this ignorance, science careers are still looked upon largely as fringe, or purely as academic exercises (with hardly any monetary future). Privilege would allow a few to seek better opportunities abroad thereby benefiting the west, instead of the Indian taxpayer’s toil that

educated them.

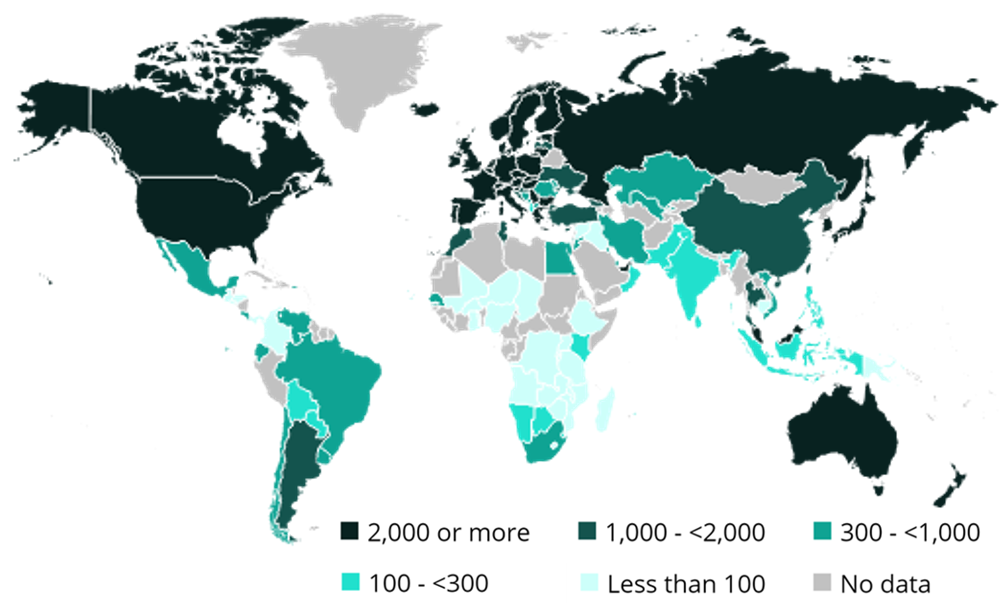

Figure 2: A color coded world map representing full-time researchers in each nation normalized to per million of the population (Source: UNESCO.org).

Yet, all is not gore. India prides itself in low cost alternatives as the messiah of underdeveloped nations. “Jugaad” has been an integral part of all things done, including pharma which does not invest on discovering new drugs, but rather makes mimics of existing ones. This helps bypass patent laws and provides cheaper alternatives to a large majority. Young english educated Indians have become our USP for human resource, a service industry for technology that we pride in. Thanks to Homi Bhabha’s vision, all governments have supported India’s space and nuclear program, which has many indigenous products under its wings. However, among all this ‘applied’ pride, the thread of underlying fundamental discoveries that builds Nobel Laurates here, are few. This leads us to a darker side of this debate! Unable to generate fundamental intellect, breaks one of the two crutches of scientific progress – Discovery! Does this make us subservient to new science and technology that is only being developed by the west? One must stop and ask, what will it take to break this cycle?

Part II – The Scientist as a COVID warrior

Evolution: the evidence at play

“Change is the only constant” – a discourse often attributed to the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, reminds us to keep our anthropocentric ego in check when we claim perfection. The human species is only a piece of the puzzle in the continuum of evolution, and change we will. Falling prey to popular misinterpretation, science-critics and faith-based believers often ask, “Is evolution real? still occurring? ….we don’t see monkeys turning into Humans”. Often, we do recognize the visible battle between predator versus prey on National Geographic; and know, that the industrial and green revolutions have helped us tap our environments. Yet, one fails to recognize that the same evolutionary battle of ‘host versus invisible parasite’ unfolds amid us as a battery of diseases. This has always maintained a threshold on human life. Something changed in the 1920s. From a prior life expectancy of ~25-30 years (on average), to a whopping 70-90yrs today, we owe this solely to the scientific discovery of antibiotics and innovations in modern medicine. But are we winning this battle? Of late, we hear of multi-drug resistant bugs that leave us bare to disease attack. Overuse of antibiotics has allowed microbes to evolve against this blockade. Even at the macro level, overuse of natural resources has increasingly narrowed the divide between the land occupied by agriculture versus the wilderness. The delicate containment of microbial infections within their isolated ecosystems was disturbed, when exposed to human endeavor. Species and their microbiomes are fighting back for survival, with diseases making proximal jumps into human societies ever so often: HIV, Mad Cow disease, Swine Flu, Nipah Virus, Bird Flu, SARS, MERS, to mention a few. The ugly face of this evolutionary evidence couldn’t have been starker than the emergence of COVID-19, that brought the world to a standstill.

Understanding this would mandate that scientists discover the principles of ecosystem biodiversity, and then innovate on sustainable development that preserves this balance. Ranking sixth among the 12 mega-biodiversity centers in the world, and with a population density of 455 people/km2 (world average 60), the need for corrective measures in India doesn’t escape anyone. Due to historic sub-compartmentalization of the sciences into zoology and botany, documenting our ecosystems has been largely qualitative or of taxonomic interest. Adding microbiologists to the furor, the modern era of genomic and metagenomic strategies make it possible to have a quantitative birds-eye view of our ecosystems, along with the invisible microbiomes therein. This creates humungous amounts of big-data, that needs synthesis and analyses from multiple angles, so that we can fit this quantitative terrain on to the qualitative jigsaw. Ecologists have stepped out of their silos and collaborated across disciplines with computer engineers, statistical modelers, and even economists! Not known to many, it is unsung public funded efforts like these, that helped to better contain the previous six jumps betacoronaviruses have successfully made into humans: 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1, besides SARS and MERS. Ecological discoveries of such fundamental nature should help not only to predict, but even innovate methods to contain future outbreaks. Are funding mechanisms in India able to arm university researchers towards a diversity of such collaborations? Are we enabling science students with an appreciation of such interdisciplinary platforms?

The elusive magic bullet against COVID-19

Why is there no cure; Aren’t scientists doing enough? From the first report in China, to sequencing the entire blueprint of the SARS-CoV2 genome, took less than two months. A pace never-before achieved in the history of science, only prior investments in infrastructure and technology development could have helped achieve this. Yes, Rome wasn’t built in a day! One of these genome sequencing technologies, took an Indian-born British scientist, Sir Shankar Balasubramanian, two decades to develop! Having invented Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) and merging it with the Swiss cluster-amplification of DNA colonies, his group established Solexa/Illumina, a sequencer that could read even the entire human genome in under two days. In sharp contrast, the first attempt to sequence the complete human genome took public funding from six countries, almost 13 years to complete (in 2003). As technology grows, the infrastructure for fundamental research also needs to be spruced up. Broadly grouped under NGS (next generation sequencing), every major University in the US possesses multiple such sequencers. In contrast, even the major state funded University of a megapolis like Mumbai, has none.

With a growing population density whose age structure is fast changing, and a tropical climate conducive to a variety of human diseases, new zoonotic jumps will likely become a harsh reality in post-COVID India. We face a diversity of gaps that need to be tackled scientifically. Paucity of funding and a lack of impetus in rebuilding university spaces, leaves the average Indian researcher ill-equipped to delve deeper into many such issues. So, it echoes, India cannot be built in a day either! Stagnating universities are stuck with technologies of the bygone era that takes years to get to a solution, rather than updated high resolution methods invented by “the west”. To recall the vicious cycle, a lack of new fundamental discoveries leaves us vulnerable to these “economic masters” of progress, who will continue to ride their inherited privileges. To add to the saga, our bureaucratic systems are extremely resilient to change; to match the pace at which problems are emerging today. Even senior scientists who have been through the rigmarole, tend to throw their hands up and blame the “system”.

But the system is us! Just as ‘evolutionary change’ allows new diseases to pop up, if our funding strategies and enabling systems do not evolve fast enough to fight back, we will be left behind. It’s common knowledge that one needs a Bio-safety-level III (BSL-3 and above) facility to do any infectious disease research. Yet, we must deal with the reality that such installations are only available in select institutions. Fewer institutions equal fewer researchers: ~156 per million in India, compared to 1089 in China and 4205 in USA. Obviously, this bleeds to a lesser diversity of problems that we can effectively tackle. Although some institutes (IISc, Tata Institutes’, IISERs’, IITs’) have seen a net increase in science funding, they only cater to the crème de la crème students of India. The plateauing size of the GDP pie and this elite focus leaves a larger majority of university students and researchers unattended. A phenomenon, Indian history has witnessed before (the educated elite of the caste pyramid), this in turn limits the diversity of ideas that we can harvest from! Fewer research institutes also mean that they are already executing select “research questions”, which directs their infrastructure and the associated projects. Many ‘central facilities’ are open for other researchers to tap into, but suffer from accessibility and available machine-time, due to the number of users they cater to. The problem is further exacerbated as many have to fend for their own maintenance and material costs. These get passed on to the end user, the common scientist, who often finds it unaffordable. With pressure to publish, pumping in their own hard-earned salaries into work related travel, participating at conferences, striking collaborations or even buying machine-time, has become somewhat normalized. Put together, these seem like a behemoth of a ‘system’ to change. Given that the expertise and infrastructure dictate the flexibility of future research, scientists find it challenging to change course suddenly, to accommodate new problems. Although the SARS-CoV2 genome sequence was made freely available, by the time India announced its first vaccine trial, the UK, US, and China were already in Phase-II of testing their candidates. Russia came under criticism as it had abridged the rigmarole and had already announced its first vaccine. Something must fundamentally change in the way we do science in India! Is the new wave of nationalism helping strengthen our systems from within? Or do we continue to gaze into our glorious past and try to reinvent the wheel?

Figure 3: Graphical representation of average Life Expectancy (aLE) from 1800 – 2019; UK (yellow), USA (green) Egypt (blue) and Asia (red). The black arrow marks Indian aLE at 25.3 years until independence (Source: Gapminder).

Ancient knowledge versus ancient science?

With the internet being everyone’s playground, social media has paved the way for a new wave of “uncensored personalized journalism”. The fringe had now gained a voice. We were happy absorbing short rhetoric via conduits like WhatsApp: ‘our ancestors had long lives’, ‘they knew of miracle cures’, and ‘had technology that would dwarf today’s western thought’! Although nationalistic in some sense, it did morph some misconceptions of “Arabic” numerals, the discovery of Zero, Pythagorean concepts and astronomy, to name a few. At a time when Europe was in the “dark ages”, Ayurveda flourished – a methodology empirically codified over hundreds of years of repeated trial and error. These were followed by similar empirical themes of naturopathy and Homeopathy. How effective were these time-tested systems: does evidence speak otherwise? Having an average life expectancy of only 25-30 years would mean, that we would enjoy a meagre 10-12 years after school education! Thankfully, the empirical method was replaced by the objectivity of testable hypothesis-driven discoveries of modern medicine. Armed with this wisdom of 100+ years of the improved scientific method, can we now discover ‘hidden hypotheses’ in ancient empirical knowledge systems? Or should we just go back to the uncertainty of empirical methods (trial and error)? Who would like to be that scapegoat? Not you, not I. The new Ministry of AYUSH was created in 2014 to streamline exactly such issues. But the same fervor that does not allow us to question our parents, our seniors, our authorities, …also apply to our revered ancient texts! ‘Why should our (ancient) knowledge be put through western tests’!? The answer stares at us, in one clear fact: in less than a hundred years, modern medicine increased the average Indian’s life expectancy to 70+ years, a number that had otherwise remained stagnant for millennia. It is obvious, that modern scientific method is not only rigorous and corrective, but also highly fruitful. But even the best scientists today, do not have all the answers! COVID-19 has bared this underbelly again! With no magic bullet at hand, the desperation to protect ourselves has driven many to reinstate faith in home remedies as the cure – but strangely enough, even for a disease that mankind had never encountered before? Who suffers from this fake information? Despite their beliefs, the privileged reap the benefits of modern medicine in the nick of time, that saves lives. The dogmatic uninformed, people who live in socially influenced cluster communities, remote villages, etc. rely heavily on home remedies, not only out of sheer faith, but also economic disparity of resources. They pay the price!

History repeats itself. Ancient medicine has been with us for millennia! But what we didn’t have when the 1918 Spanish flu hit us, was modern medicine! A hundred years ago, people behaved exactly the same: the Flu spread along the major trade routes (railways), possibly because of migrant laborers who fled the diseased metros. India saw a first wave of the flu in the summer, but a much larger and lethal wave by December. Wouldn’t it be prudent to revisit all the factors that left us vulnerable to the second peak, rather than fund the testing of dogmatic benefits propagated by social-media-medicos?

The way forward

Why are we always playing catch-up? History of India’s science funding highlights three problem areas: (1) The small percentage of public-funding (% of GDP); (2) Poor academia-private partnerships; and (3) A change of focus to enable the larger university system with updated research facilities and training. For every dollar cumulatively spent by the Chinese, we invest less than $0.14 towards science. Factoring in the number of scientists per million who get these funds, each Indian scientist should’ve been almost three times richer than their American counterparts. Clearly that is not the case! Does this point to an “income-inequality” in granted funds among Indian researchers: i.e. science funding really goes to a focused (privileged?) few! Are they just building on their privileges – better publications attract better funds? Or does both government vision, as well as amount of science funding, need a deeper overhaul?

Over the last two decades, governments have instated awards like the prestigious INSPIRE, Wellcome-DBT Alliance, Ramalingaswami, and Ramanujan fellowships, to reverse brain-drain. Of particular mention in the past two decades, is the rapid expansion of technology hubs like the IITs and the establishment of new fundamental research institutes like the IISERs, NISER to mention a few. Although fewer laurels go to discovery, thanks to the service industry, India emerged as a world leader in vaccine production. Once the designs by UK/US labs are validated, many eyes will turn to India for ramping up production. Early on, Indian companies produced PPE kits, while scientists developed modern technology for indigenous detection kits (LAMP, CRISPR etc), that are awaiting ICMR approval.

The question though, is not about a few beacons of glory. India has been projected to become the most populous country by 2024, while nature’s vehemence of climate change and global warming, keeps altering disease landscapes in unpredictable ways! “Are these efforts enough for a good future?” – a pertinent question in the post-COVID era. I argue that the key is in increasing the diversity of research areas, and achieving a critical mass of well-funded researchers across the country, which will trigger discovery! This would call for targeted funding of research infrastructure of state-owned universities or even private universities, that are currently no match to their American counterparts. Recent models like CEBS-Mumbai are being tested to reinstate a research environment within the archaic university ecosystem. Maybe we can achieve such middle ground, by adding enabling mechanisms that require established research institutes to adopt a few smaller university systems and help rebuild them from within. If successful, can that be quickly replicated across Indian universities? Can COVID-19 imposition of electronic connectivity help us to think out-of-the-box?

Tangible solutions?

There is no such thing as Ancient Science and Western Science. We need to act in sync with our constitutional responsibilities and evaluate every claim, based on a common benchmark of scientific temper! Education should be enabling us to question, what we deem scientific. Based on deeper introspection and the discussions presented here, I list a few suggestions that might help going forward:

(a) Increase public funded research to at least 3% of GDP, maintaining a large impetus on much needed basic research: Build evaluation procedures for blue sky research on the merit of their ideas, uniqueness and experimental implementation towards building on their hypotheses – does their research push the boundaries beyond existing knowledge? These checks will likely arm us with avant-garde discoveries, and therefore have the potential to generate new IP/technology; (b) Build attractive propositions for private investors to match funding in government aided institutes – with different incentives towards blue sky versus applied research; this will aid the much needed crosstalk on: How market expectations can be fulfilled by university graduates; (c) Evaluate applied-researchers for vertical projection of their research, and not just for publication-heavy output which keeps expanding laterally without achieving fruition at the marketplace; Encourage vertical collaborations with industry with high-risk:high-reward patent funding; this will encourage free-market entrepreneurship and start-ups. (d) Restructure administrative policies: With increasing average age of the population, age restricted policies and archaic guide-ship rules in most universities need overhaul. With longer life-expectancy and inter-disciplinary careers, 35+ year old academic researchers find themselves ineligible for many funding programs or find it difficult to shuttle back from non-academic spaces; we have to remember, ideas aren’t limited by age or origin. (e) Fill up the faculty vacancies abundant in university systems, which forces them to employ stop-gap teachers with lesser experience, further lowering the standards of research and education. Provide attractive funding packages to reverse brain drain at these posts. (f) Enable the underprivileged with scholarships/funds, especially women and the economically marginalized, to help bridge both social and gender-sexuality divide in science.

Last but not least, there is one crucial nail in the coffin, that I believe will help in achieving the above: engaging scientists in all fields of policy making! Bureaucrats are great at bringing information and analyses to the table, but scientists are good at using objectivity for building new hypothesis, and testing them. Most importantly, when 9 out of 10 experiments do not work, scientists do not look at them as failures. In fact, failing is an integral part of the scientific process, because each failure will cut-off an unwarranted diversion early on, thereby steering the path towards fruition. Constitutionally speaking, we should base all decisions on evidence; not dogmatic ideologies or flair filled projections. Let open debate become a part of the process once again! Of course, this is not going to be cakewalk! It will require diversion of funds from existing resources, towards scientific research. That is where bureaucrats, politicians and scientists really need to scour the evidence at hand. I would envisage a future, where lawmakers and scientists come together to shape a body of “Science governance”: a lawfully abided by independent governing body of scientific method that will oversee all branches of science: from inductive reasoning to deductive methods, from molecular medicine to alternative approaches. Unless we abide by a common benchmark of scientific temper, pseudoscience and WhatsApp medicos will continue to flourish and create harm.

Our Honorable Prime Minister’s clarion call for an ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’ can only be realized by planning for self-reliance in the vision. Yes, we have a long way to go, but all is not lost! ….For now, COVID-19 has caught us by our tails! How quickly we can turn the situation around, really depends on how we develop a strongly funded backbone that is yet bureaucratically flexible enough, to turn and fight back!

Subhojit Sen is a Ramaligaswamy Fellow and a faculty hosted by the UM-DAE Centre for Excellence in Basic Sciences, Mumbai. Views expressed are personal.

This article is part of a series called “Academics Post COVID-19”. The other articles in the series can be found here.

Ketaki Joshi says:

Something very interesting and important, I am going to recommend my few friends to read this.

Sonali Sengupta says:

Highly insightful and constructive. Relevant recommendation-Need to increase research funding to atleast 3% of GDP. Also need to spread the idea to the public that there is no such thing as ancient science and western science as separate categories.

Pradeep Uchil says:

After YouTube videos on COVID-19 fact checks and myth busting to inform the general public during uncertain times, here’s one very informative, in-depth and solution-oriented piece by Subodh to take Indian Science forward!